Digital currencies :the ultimate soft power?

Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are the vehicle for central banks worldwide to develop their own digital payment alternatives. Not only are emerging market economies ahead of developed ones in launching them but CBDCs are also emerging as a soft power tool at a time of geopolitical volatility. flow’s Clarissa Dann provides a summary of a recent Deutsche Bank Research report

In a speech given on 17 April,1 Sir Jon Cunliffe, deputy governor at the Bank of England (BoE) predicted, “If future trends continue, cash use is likely to decline further and cash itself will become less useable in all everyday transactions; for example, if internet commerce grows and if merchants increasingly accept only digital payment.”

Potential outcomes include the launch of a UK central bank digital currency (CBDC) – a sterling digital currency that would be issued by the BoE for general purpose retail use, said Sir Jon. “No decision has been taken to implement the digital pound, but the Bank and Treasury’s assessment is that it is likely to be needed if current trends in payments and money continue.”

Deutsche Bank Research analysts Marion Laboure and Cassidy Ainsworth-Grace examine the CBDC initiatives of various central banks in “Digital currencies: the ultimate soft power?”; their latest white paper of the series The Future of Payments, published on 12 April.

As flow reported in ‘Digital assets – from exuberance to utility’, both believe that while Bitcoin could emerge as the “North Star” of the cryptocurrency market, many of its peers are driven more by “magical thinking” than practical considerations, having yet to prove they offer any added value. Nonetheless, cryptos’ growing popularity could pose a challenge to the monetary sovereignty of the world’s central banks and potentially risk “increasing conflicts between private crypto assets and central banks over monetary control” say Laboure and Ainsworth-Grace.

The CBDC race: drivers, leaders and laggards

The response to crypto from central banks in both developed economies and emerging market economies (EMEs) is to develop digital payment alternatives via a CBDC.

“EMEs seem to be leading the charge, with mixed success, but advanced economies are following closely behind,” the report reflects. Yet not all countries are converts to the cause. The Bank of Israel’s (BoI) steering committee, which issued its 21-page report on 17 April assessing the viability of a digital shekel, notes that although 90% of the world's central banks are examining CBDCs, only a handful have yet actually issued one.

Like several of its peers, the Bank of Israel is hedging its bets. Along with the central banks of Norway and Sweden it has teamed up with the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) to study how CBDCs might best be used for international retail and remittance payments. The BoI also wants to see how far and how fast the US and the European Union (EU) progress with their own CBDC initiatives and is assessing factors including the declining role of cash, the use of stablecoins, competition in the domestic payment system and technological developments in payments systems.

Laboure and Ainsworth-Grace add US-China tensions as possibly the biggest single driver in accelerating CBDC development. “Geopolitics have prompted a re-evaluation of the current international financial system, and some countries may position CBDCs as a soft power tool – potentially upsetting the dominance of the US dollar and SWIFT,” they suggest.

Cited as a recent example is Russia’s plan to launch a retail CBDC. In February the Bank of Russia announced that the roll-out of the digital rouble was being accelerated to 1 April 2023 rather than 2024 in a bid to blunt the impact of Western sanctions. With most of Russia’s financial institutions expelled from SWIFT since conflict in Ukraine began in February 2022, the digital rouble is also seen as offering an alternative to the network and a means to reduce Russia’s dependency on the US dollar. However, shortly before 1 April, the launch was postponed to an unconfirmed future date.

All these developments are likely to contribute towards a decoupling between the US and its allies as well as China and its allies, the authors suggest, and will “likely lead to fragmented internal payments, resulting in a surge in complexity and expense”.

Digital cash momentum

Meanwhile the question has moved from whether digital cash will arrive, to when and how? Three factors have spurred CBDC projects:

- Cash is losing ground as a payment method, a trend accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic. From March 2020 to December 2021, 60% of central banks recorded a decline in cash usage in their jurisdiction;

- Facebook (now Meta) announcing plans in June 2019 to issue its own currency, Libra, coupled with the emergence of private cryptocurrencies, which pushed central banks into action (the project was later suspended); and

- US-China trade and tech tensions have sped up CBDC development. Geopolitics has triggered a revaluation of the current international financial system, and certain countries may position CBDCs as a soft power tool - potentially upsetting the dominance of both the US dollar and SWIFT.

With most of the world’s central banks engaged in some form of CBDC work, 62% are experimenting at the proof-of-concept stage, and 68% could issue a retail CBDC in the medium term. Just over three quarters of those nations working on a retail CBDC are exploring interoperability with existing payment systems, to encourage the coexistence of central bank and commercial bank money and accelerate widespread adoption of CBDCs.

The pioneers

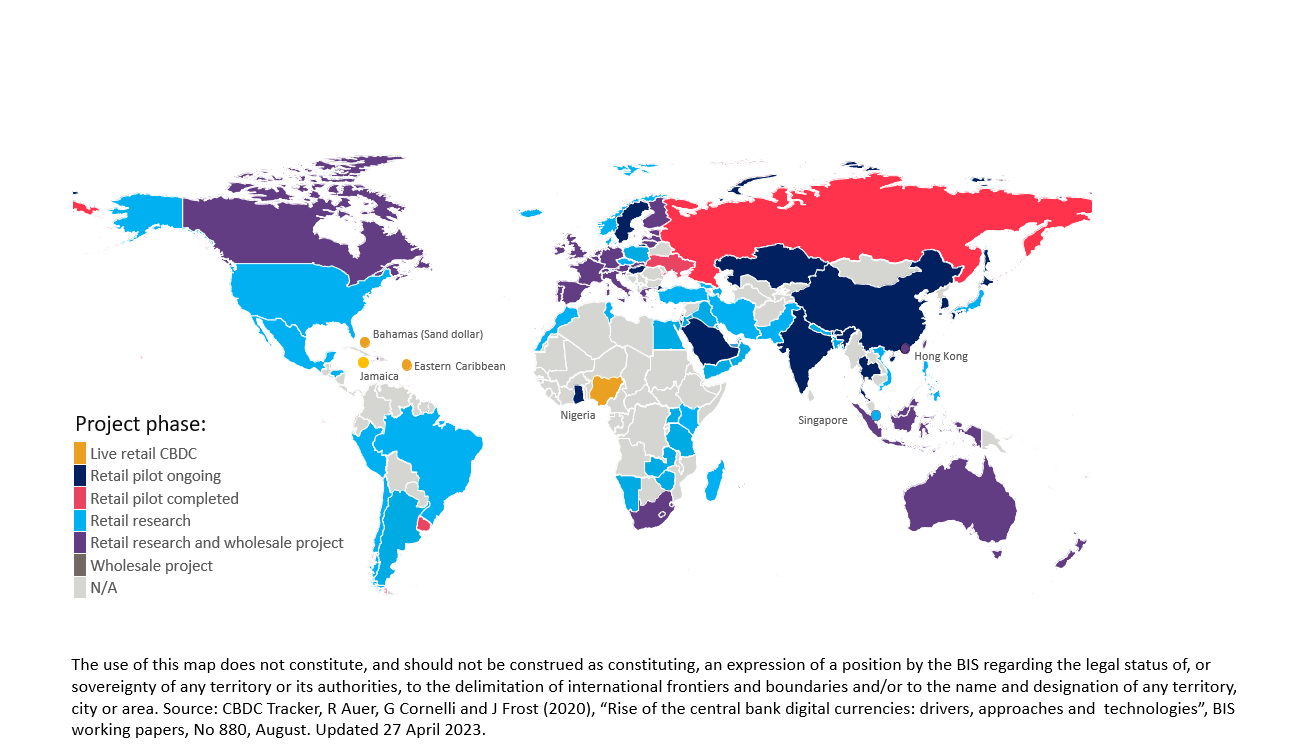

Figure 1: CBDC projects around the world

EMEs were first to move from CBDC experimentation and pilots to launch. The Bahamas, Eastern Caribbean, Jamaica and Nigeria have live retail CBDCs, reflecting large young demographics and often unbanked communities, a proliferation of mobile phone usage and the popularity of peer-to-peer (P2P) payments.

Yet while EMEs lead the race, their domestic uptake of CBDCs has proved less enthusiastic than anticipated, due largely to persistent old payment habits.

As flow reported in “CBDCs: what’s not to love?” (April 2022) the Bahamas launched its retail CBDC, the Bahamian Sand Dollar, in October 2020. Pegged to the US dollar, the BSD is based on digital ledger technology (DLT) with a hybrid wireless network to connect mobile devices.

The country would seem to be a strong contender for CBDC adoption, with 18% of Bahamians unbanked and severe weather regularly disrupting cash distribution. However, early interest in the BSD quickly levelled off. By Q3 2021 circulation had plateaued and in mid-2022 only about 30,000 BSD wallets were in use: an adoption rate below 8%. “The slowdown is surprising in a country with 90% penetration for mobile devices, but surveys find 77% of Bahamian firms confirming chequing accounts as still their most utilised payment method,” note Laboure and Ainsworth-Grace.

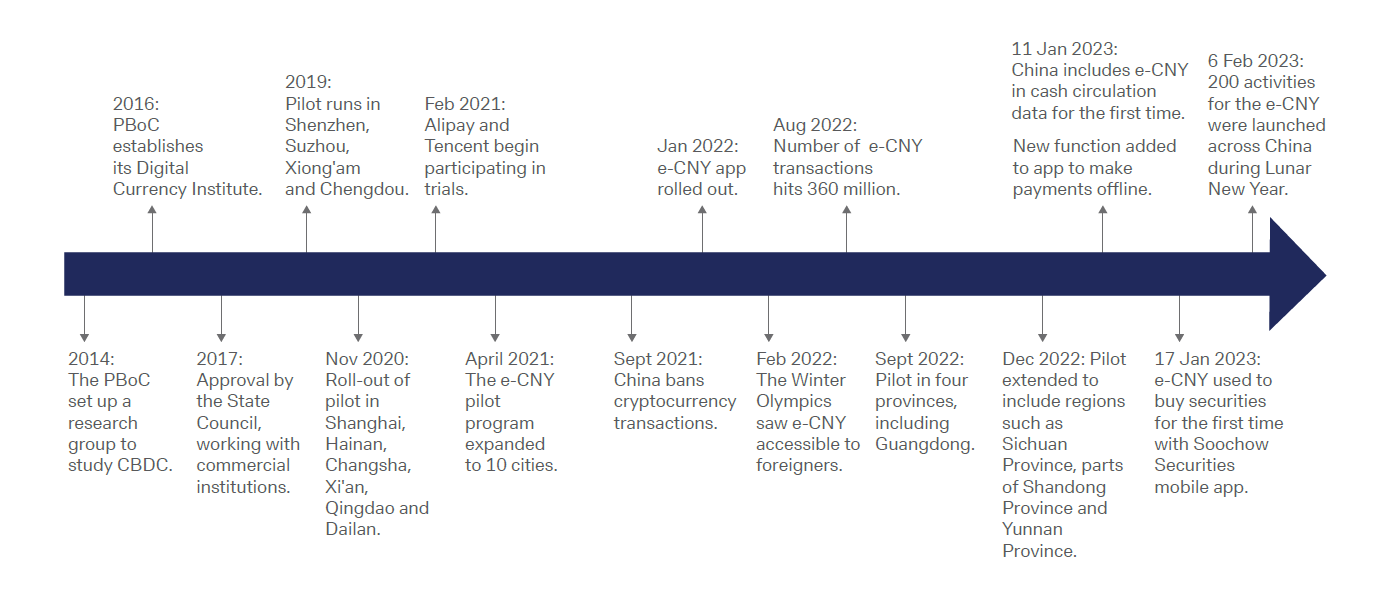

The islands’ efforts are dwarfed by China, which began researching and developing a CBDC in 2014 and by 2019 had launched a pilot in the regions of Shenzhen, Suzhou, Xiong’an and Chengdu, adding six more regions during the Covid-19 pandemic. In September 2022, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) extended the trials to four provinces, including the populous Guangdong, while the Beijing Winter Olympics in February 2022 saw the digital yuan (e-CNY) marketed to visitors for the first time, when it was used in daily transactions worth renminbi (RMB) 2 million (US$ 315,000).

Figure 2: Timeline of the development of China's CBDC

Sources: Deutsche Bank, PBoC

As the authors note, China has credentials for successful CBDC experimentation – a young, tech-savvy population and – since the mid-2000s – a direct switch from physical cash to mobile payments, now established as the payment method of choice with 65% of all transactions in 2022. Both the government and the PBoC have provided backing and infrastructure to support e-CNY usage. Fintech platforms Alipay and Tencent joined in February 2021, when both began participating in trials to offer services through the e-CNY.

Yet China’s domestic uptake is also sluggish. In June 2021, fewer than 71 million digital wallet transactions were recorded, with a value of RMB 34.5 billion, equivalent to 0.04% of total RMB in circulation. By August 2022 monthly transactions were at 360 million, valued at over RMB 100 billion, but last December saw e-CNY transactions still only represent 0.13% of currency in circulation.

Early CBDC adopters also include the East Caribbean, Nigeria and Jamaica. In April 2021, the Eastern Caribbean launched DCash, the first digital currency used in a monetary union, with eight of nine member states participating. The CBDC has no transaction fees and aims to facilitate digital money transfers made to consumers and merchants. An early setback in January 2022 saw the DCash programme crash due to an ‘expiring certificate’ on the Hyperledger Fabric that hosts the CBDC, and the digital currency was offline for eight weeks. The Eastern Caribbean Central Bank intends to introduce an e-commerce function so businesses can accept DCash via websites and in February engaged a local marketing agency to promote the scheme.

Nigeria became the first African nation to launch a CBDC in October 2021, with the release of the eNaira. Initially only individuals with a bank verification number could open a wallet (about 26% of the population). While the Central Bank of Nigeria targeted eight million users by August 2022, fewer than one million Nigerians (of 220 million) adopted the digital currency. A cash crunch last December, when insufficient new banknotes were printed to replace withdrawn ones, sparked major demand for alternative payments - including the eNaira. Reports show there was a 63% surge in the value of eNaira transactions to 22 billion Naira and 13 million more wallets have been opened since October.

Jamaica followed, launching its own CBDC – the Jam-Dex – in July 2022 through digital wallet the Lynk app, while the Bank of Jamaica offered a $16 incentive for the first 100,000 users. Activating wallets required users to upload one government-issued photo ID and a copy of their taxpayer registration number. The Bank of Jamaica also implemented a public education programme under the banner “No Cash, No Problem.” By August 2022, there were more than 120,000 users and over 2,300 merchants on the Lynk platform. More recent rollouts to new wallet providers saw JN Bank onboarded last December, after receiving US$1m in CBDC from the central bank.

Further back: the Eurozone, the UK and the US

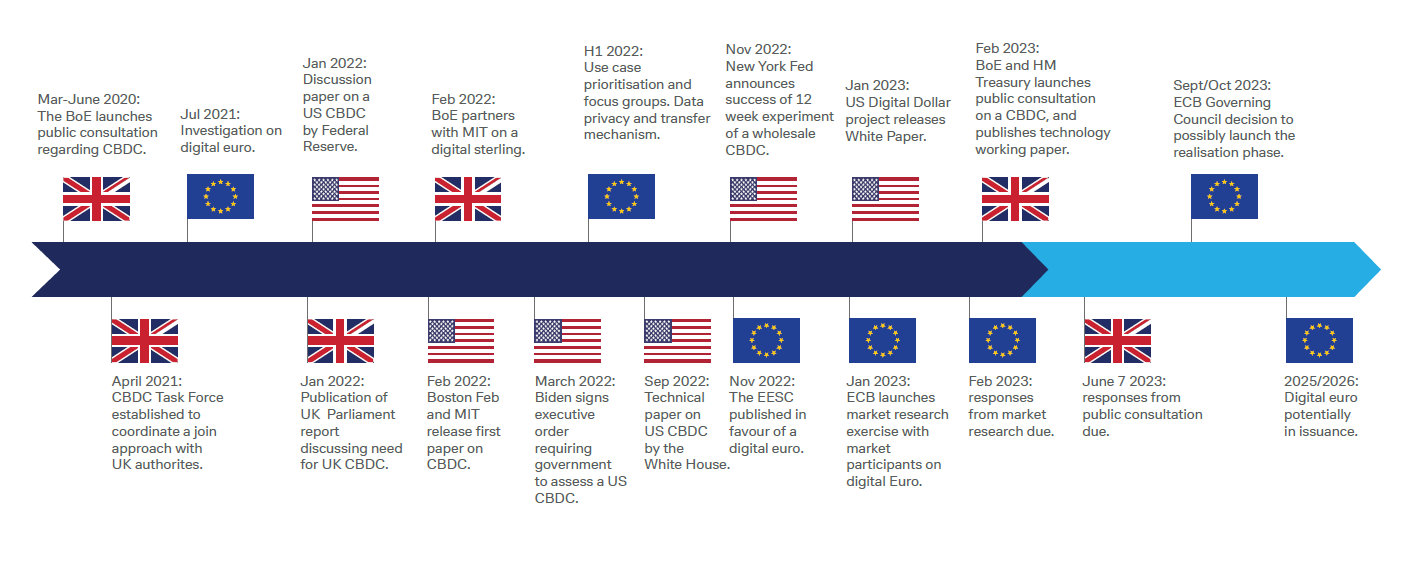

Figure 3: Timeline for CBDC projects in the Eurozone, the UK and the US

Sources: Deutsche Bank, ECB, BoE, US Federal Reserve

Laboure and Ainsworth-Grace describe developed economies as the “runners-up” in CBDC development; more concerned than EMEs with how they fit into established legal frameworks and in preserving monetary authority.

Leading “the pack” is the European Central Bank (ECB), which focuses on monetary sovereignty and increased efficiency in payment systems across the Eurozone. In October 2021 the ECB launched a two-year investigation phase to address key issues related to the design and distribution of the digital euro. Once completed, the Governing Council will decide on whether to launch the realisation phase. ECB President Christine Lagarde indicates that a digital euro could be ready by 2025–26, although members of the European Parliament did voice scepticism on whether the project is worth pursuing.

The UK remains undecided on whether to introduce a CBDC, although on 7 February the BoE and HM Treasury jointly launched a public consultation paper on a retail CBDC (digital pound)2 that outlines design considerations and concludes a digital pound will likely be needed in the future. No concrete timeline has been released though, and the BoE continues to research the viability of launching a CBDC.

In the US, the Federal Reserve System is similarly non-committal, although there have been efforts to explore the viability of a CBDC and in March the Biden administration released an executive order on ensuring the responsible development of digital assets. Since 2020, the Boston Fed has collaborated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Digital Currency Initiative on the CBDC framework, releasing their first paper on ‘Project Hamilton’ in February 2022.3 In November, the New York Fed also issued a report on an experimental wholesale CBDC.

A global economic uncoupling

The dollar remains the dominant currency globally, but China is working to internationalise the RMB, with the e-CNY a soft power tool that may be used to achieve its aims, the report explains. This project is driven by twin factors – necessity caused by America’s willingness to use the USD as a tool to sanction countries; and growing confidence in the RMB, particularly due to its expansion into key export markets and the e-CNY. It could ultimately contribute to “a global economic decoupling that could divide the world into the international blocks of the US and its allies, and China and its allies,” say Laboure and Ainsworth-Grace.

The US has demonstrated its willingness and ability to freeze USD reserves in Iran, Venezuela and Afghanistan and in February 2022 it added around half of Russia’s foreign exchange reserves.

Beijing is now expected to accelerate its de-dollarisation efforts in response. Over four decades, China has taken an essential position in global trade, becoming the biggest exporter of goods in 2009 and the largest trading nation globally. This success has been underpinned by a policy of reducing its exposure to the rest of the world while encouraging the world to increase its exposure to China. Additionally, in 2016, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) added the RMB to the Special Drawing Rights (SDR) reserve basket, making it a de jure international currency.

Although the PBoC is focused on e-CNY’s domestic use, there is growing assurance that in the long-term internationalising the RMB may not require sacrificing monetary sovereignty. The e-CNY will likely soon accommodate small, cross-border transactions, with the CBDC now available in Hong Kong.

Alternative payments systems

While China’s efforts won’t immediately challenge the global monetary order, “in our view, the development of alternatives to the hegemonic SWIFT may represent a crucial step forward in a global decoupling”, reflect Laboure and Ainsworth-Grace.

However, CIPS, the Bank of Russia’s financial messaging system SPFS and India’s Structured Financial Messaging System (SFMS) are yet to become major competitors. Indeed, 80% of payments made through CIPS use SWIFT messaging, while CIPS had 1,427 participants in March 2023 against SWIFT’s 11,000. In terms of its clearing function, the US clearing house system CHIPS processes 40 times as many transactions than CIPS for 10 times as many banks.

Yet looking further ahead, CIPS may hold significant future potential. China is well-positioned for success via its Belt and Road Initiative and African investment activity. Also mooted is a possible linking of Russia’s SPFS with China’s CIPS, which would allow both to circumvent US sanctions and transact mutually and explain the report’s authors, is likely to contribute to the global economic decoupling they predict.

Although China’s e-CNY project is making slow progress, it is, say Laboure and Ainsworth-Grace “evident that the CBDC may be used as a soft power tool to internationalise the RMB”. They conclude, “We believe that 2023 could represent a turning point in US-China relations, and against this backdrop, CBDCs may function as a new soft power tool to achieve both economic and geopolitical aims.”

Deutsche Bank Research report referenced:

The Future of Payments, Series 4 - Part 1. Digital currencies: The ultimate soft power? by Marion Laboure and Cassidy Ainsworth-Grace (April 2023)

First, please LoginComment After ~